August 16 – September 27, 2020

Virtual ceremony on Zoom,

Livestreamed to Facebook and Youtube: April 23, 5 – 8 p.m.

Contemporary Native Art Biennial (BACA), 5th edition

Kahwatsiretátie : Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie

Honoring kinship

Curated by David Garneau (Métis), with the assistance of rudi aker (Wolastoqiyik) and Faye Mullen.

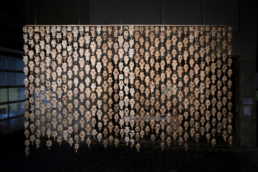

Artists: Judy Anderson, Cruz Anderson, Scott Benesiinaabandan, Rainer Wittenborn & Claus Biegert, Catherine Blackburn, Katherine Boyer, Bob Boyer, Kaia’tanó:ron Dumoulin Bush, Warren Cariou, Hunter Cascagnette, Hannah Claus, Renée Condo, Jon Corbett, Ruth Cuthand, Wally Dion, Devonn Drossel, Marcy Friesen, Lucas Hale, Emma Hassencahl-Perley, Larissa Riss Kitchemonia, Sharon Rose Kootenay, Owisokon Pauline Lahache, Tania Larsson, Jason Edward Lewis, Kay Mayer, Kevin McKenzie, Dylan Miner, Nadia Myre, Margaret Orr, Graham Paradis, Luke Parnell, Sage Paul, Jobena Petonoquot, Sherry Farrell Racette, Diane Roberts, Sonia Robertson, Máret Ánne Sara, Nancy Saunders, Skawennati, Marian Snow, Jack Theis, Ulivia Uviluk, Flora Weitsche, Corinna Wollf. Weaving Cultural Identities: Threads Through Time: Efemeral, Chief Janice George, Angela George, Doaa Jamal, Buddy Joseph, Krista Point, Ruth Scheuing, Debra Sparrow, Robyn Sparrow, Mary Lou Trinkwon.

Venues: Art Mûr, La Guilde, Musée McCord, Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, La Galerie d’art Stewart Hall

Artists exhibiting at Stewart Hall Art Gallery: Warren Cariou, Kay Mayer, Dylan Miner, Margaret Orr, Sonia Robertson, Máret Ánne Sara, Rainer Wittenborn & Claus Biegert

Stewart Hall Art Gallery

176, chemin du Bord-du-Lac – Lakeshore

Pointe-Claire, Quebec

David Garneau

Prior to French and British invasion, people in Northern Turtle Island belonged to separate nations speaking more than ninety languages. They traded, warred, made treaty, inter-married, or lived so far from each other that they never met. However, imperialist rhetoric corralled them as one people, Indians. The racist epithet legislated disparate peoples into a common and degraded body. It was but one of the tools used to divide settlers from Natives, and Natives from land. In the early twentieth century, some tried to rehabilitate the word as a symbol of collective resistant agency. The Canadian National Indian Brotherhood, for example, organized leaders from coast to coast and tree-line to Medicine Line. However, in the 1980s, they renamed themselves The Assembly of First Nations. Too freighted with negative associations, the mistaken and imposed label, Indian, faded and Aboriginal, for a time, was the preferred collective noun for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. This renaming signaled a shift in self-understanding and collective being.

To consciously identify as Aboriginal, Native, or autochtone means that in addition to being, for example, Kanien’keha:ka, Inuvialuit, or Métis, you purposefully align yourself with all non-settler peoples in the territory now known as Canada. Aboriginal is a political identity when chosen rather than decreed. Wearing it recognizes that we are not only shaped by our home communities but also by, and in collective resistance to, a colonial nation. To reject the name Indian is to see yourself as something more than an Indian as defined by the Indian Act.

Recently, Indigenous—as in The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples—is the current preferred collective noun. Indians were wards of the state. Aboriginals struggle to gain or maintain self-governance, for sovereignty within but apart from a specific colonial nation. Indigenous people take this a step further and identify with First Peoples around the globe. Indigenous is an inter-national identity uniting people Native to different territories but who nevertheless share worldviews and imposed colonial experience. Indigenous is a name for the world-wide struggle to restore natural law, which includes the end of colonialism, patriarchy, predatory capitalism, racism, and environmental degradation. Indigenous people rejuvenate non-colonial practices and adapt them to the present age and their specific location.

While Native nations, iwis, tribes, etc., are communities bound by blood, language, tradition, ceremony, and territory, there was always fluidity in these relations. They were enriched by inter-tribal marriages, adoptions, and migration. The development of rapid communication and travel has further increased the web of Native relations. In the Indigenous era, kinship includes not only blood, soil, and non-human relations but also extra-familial, extra-territorial, even virtual kin. For those whose communities are devastated by aggressive assimilation—by Indian Residential Schools that sought to exterminate Indigenous languages and culture by separating children from their families and re-educating them into non-Native ways of knowing and being; by Christianization of the sort that demonizes traditional spirituality, gender fluidity, and non-patriarchal societies; and predatory capitalism that ruins ecosystems, displaces and divides communities, and creates wealth disparity; for those families that continue to struggle with the fallout of genocide, who suffer poverty, food and water insecurity, substance abuse, violence, suicide, children seized by government agencies, adopting out, and disproportionate incarceration—for these folks, family and community relations may be untenable. Some need to create kinship beyond kin, connect to communities and people to find like minds and actions; to find and give support.

The 4th edition the Contemporary Native Art Biennial (BACA), níchiwamiskwém | nimidet | my sister | ma sœur, curated by Niki Little and Becca Taylor, explored the relations between Indigenous women that extend beyond blood. The 5th edition of BACA continues to bead this thread. Curated by myself with the support of rudi aker (Wolastoqiyik) and Faye Mullen, Kahwatsiretátie features the work of more than fifty artists in six Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montréal locations who engage intergenerational relations, alignment with ancestors both past and future, connections with other than human beings, folks looking for ’home’ in territories not home to their ancestors, friendships, and mentor and mentee affiliations, among other interrelations.

Recognizing that these exhibitions take place on the traditional and unceded territory of the Kanien’keháka, and that Faye, rudi, and I, and many of the artists, are not from here, we sought council with the stewards of this territory. We, and the BACA Board, met with Elders and artists at the Mohawk Trail Longhouse in Kahnawà:ke to begin an alliance. In a subsequent meeting with Faye, Elder Otsitsaken:ra (Charles Patton) and Faith Keeper Niioieren (Eileen Patton), entrusted us with the title Kahwatsiretátie: Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie. The words picture a continuous circle being held together hand in hand, nation to nation, lifting weight together. These Kanienʼkeha words carry the values of a sustained kinship, of continuously holding matter together. BACA 2020 endeavours to give material form to these words, to express the interconnectedness of all things while acknowledging that sustaining good relations is a weighty matter, and is a matter of will, love, kinship, and friendship.

An important aspect of maintaining good relations is reciprocity. We came to the community to ask for their blessing, and to ask them to open Kahwatsiretátie. BACA offered to provide transport for community members who want to visit the exhibitions, and we commissioned Kahnawà:ke beaders to create gifts for all the artists. At the Longhouse, we connected with community artists and have included them in the show. Ongoing reciprocity between urban and reserve communities will be sustained throughout the months of BACA. This will take the form of gatherings, workshops, hide scrapping and garden projects that Faye is working with the community of Kahnawà:ke and Kahnestà:ke to build. Kinship includes Indigenous people from different nations meeting each other’s needs where they are. It is an open heart, an open hand, and a promise of future engagement.

Kinship is not just the subject of Kahwatsiretátie, it also informs our curatorial method. In addition to choosing fine works of art and placing them in good display relations with each other, we also asked many of the senior artists to invite “kin” to exhibit with them. These may be family, community members, mentees, or other kindred folks. This redistribution of curatorial agency is a form of non-colonial practice. Like a ceremony or party where invited guests invite their own guests, we want to expand the circle to include relations we did not yet know. As a result, Kahwatsiretátie includes a few artists who have never shown their work in Quebec, or outside their community, or as art.

Kahwatsiretátie includes a full range of art media: drawing, painting, ceramics, sculpture, photography, audio installations, video, digital media, performances, etc., but there is an emphasis on beading and textiles. A substantial aspect of the Indigenous renaissance is the resurgence of traditional art forms repurposed to include engagement with contemporary experience. Beading is accessible. You don’t need an MFA to pick up the skills and make something special; though having a mentor helps. It is also accessible in that beading occurs in nearly every culture. Everyone appreciates beautiful handmade things. Most of our beads come from beyond Turtle Island, as do some of our patterns. Beading is a metissage, a mixing of materials and influences. Making by hand, using traditional techniques learned from watching and doing, creates a haptic connection with previous generations.

While Kahwatsiretátie certainly has a lot of things in rooms, an equal focus is on relations beyond objects. We are also interested in the people in these rooms—and outside of them—in music, performance art, workshops, talks, panels, and other gatherings in and around the exhibitions. Kahwatsiretátie: Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie reverberates with a phrase familiar within Native circles. “All our relations” is evoked at gatherings to acknowledge persons present and absent and includes non-human beings as kin. It recognizes the privilege of presence. Faye, rudi, and I have been invited to curate these spaces and relations. In two years, it will be other people, other works, and other ideas. While we take our roles seriously, and bring our best selves here, it is with humility. We are visiting, not settling in these places.

Sovereign Indigenous display territories are permanent or contingent sites where the display of Indigenous creative production is managed by Indigenous people. In the case of BACA, we temporarily occupy spaces not ours to offer glimpses of what is ours. Art, in the sense of special human-made things and performances separated from everyday life and touch, and put in rooms for ocular contemplation, is a colonial habit. A challenge of working in these spaces and with the legacy of these habits is to find ways to indigenize them. Indigenization, as it is currently practiced in the TRC era, usually means bringing Indigenous teaching and things to non-Native places like universities and museums under the institution’s terms. Ironically, this appropriation is the opposite of the original sense of indigenization, which was the idea of Native people taking and adapting those aspects of colonial culture that suited their needs. At our best, we work with these spaces and their keepers to develop new modes of curation based on Native ways of knowing and being. Each exhibition is a step toward creative sovereignty.

i. These last three sentences are Faye Mullen’s understanding of the teachings gifted her from Elder Otsitsaken:ra (Charles Patton), and faith keeper Niioieren (Eileen Patton).

Faye Mullen & rudi aker

We gather for Kahwatsiretátie : Teionkwariwaienna Tekariwaiennawahkòntie on unceded Land. Land that has sustained ecosystems and complex relationalities far beyond human existence. These Lands and Waters have braided kinship relations with our four-legged relatives, the deer, bear, skunk, fox. The swimmers and the winged ones: eagle, hawk, crow, heron. The insects and the web-maker themself: spider. Our relatives that carry the teachings of living between worlds: the cocooned caterpillar becoming a butterfly, the turtle, beaver, snake. The Land has nourished and been sustained by plants + medicines, needled and leaved trees. The rain and thunderers. By Sun, the four Winds, and Moon.

This place with which we gather has been in relational care and reciprocal response with Indigenous peoples since time immemorial.

To maintain our personal and collective relationalities, it is crucial to think long and often about how we come to be in, be of, and be with territories. As Indigenous peoples, we are often, electively and otherwise, defined by the Lands from which we were birthed, the rivers that sustained us, the plains laid open for Ancestors. Our kinship ties span further than only those with our blood and chosen families; they travel into deeper realms of relations with non-human beings: animals, elements, medicines and beyond.

Being from a place and being of a place opens a dialogue that is full of, yet not entirely articulated through semantics and other means of speech. Though, here, we take to writing.

We hold obligations, as members of nations distant to this Land, to move carefully, intentionally, and generatively. While regionality is negotiated as a marker for who and how one comes into being, we must acknowledge the forces which have moved us and allowed us to be here, uninvited. We aim to tread respectfully across these Lands that hold us to cultivate authentic and palpable possibilities for ongoing relations in which we committedly center gratitude, trust and care. In the gatherings that we have been fortunate to facilitate and participate in, it is not without active consultation and guidance with members of communities which we are, again, privileged to be a part of. Elder and Faithkeeper of Mohawk Trail Longhouse in Kahnawà:ke, Otsitsaken:ra and Niioieren, awoken the Spirit to accompany the role of Ie’nikónirare in Faye, a pathfinder who continuously minds the thinking and carries the teachings of our relative, Wolf. Through temporalities beyond the present continuum, we have been woven into a work that is collective. One might call on how all of these gatherings formed themselves, synchronistic, though it is far from that, acknowledging that the English language holds not a word for Ancestor-led.

A web of relations is nourishing, supportive and acknowledges the Spirit well before the body, identity or social status. A web sustains kinship ties and heart threads to human and other-than-human relatives alike—maintaining a balanced understanding that no species is prioritized. Threads, in proximity to one another and in their flow, effect and affect one another. The tender emotions and currents of care within one thread directly influence interconnected threads and so, too, the web as a whole. Vast kinship in the making. A web implies a center point and there is commitment to an understanding that the focus is not an individual nor a sole being. Spider reminds us that the center point is a path, a lifework, an intention laying on the ground—the center point is and has always been the Land.

In all of its forms and permutations, kinship is not only a relational modality but, more operatively, a way of being and thinking. In a place like Turtle Island, as those Indigenous to this place, our ontologies have been tried and tested yet have endured the battles of contact, colonization, assimilation, genocide and ecocide. Indigeneity is not a weight, nor a burden, nor a singular identity but rather a testament of our survivability, our resilience, our power. We aim to recognize and relish the intersections of communities and nations when thinking of ourselves as a unified people, “Indigenous” people—a move in alliance to regaining and maintaining kinship ontologies that have and will continue to exist within all of our temporalities despite the state of our homelands.

Many First Peoples consider Tiohtià:ke + Mooniyaang as homeland, traditional territory, birthplace, gathering place, sacred site and burial grounds of their people. We wish to respectfully acknowledge the lineage of nations who have held relations with this place: the Kanien’kehá:ka of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, Huron/Wendat, Abenaki, and Anishinaabe – whose bones we walk over. These nations are recognized in reciprocity with the Lands and Waters and the continuous stewarded relations honoured by the Kanien’kehá:ka, communities of Kahnawà:ke and Kanehsatá:ke. There are no agreements or treaties that were transferred from any Indigenous Nation to settler ownership or control. The Land was and continues to be occupied without permission, or consent. Since contact, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples and nations from their Lands, Waters, and Sovereignty was committed violently and remains to be the foundation of the state.

Ongoing settler colonialism on stolen Indigenous Land is upheld by this nation state — while territories are decomposing under our fingernails, we carry the weight of grief work in action.

Positioning ourselves as Indigenous resurgent practitioners while acknowledging our implication within a cultural landscape that is bound to the capitalist market, we maintain a responsibility to form pathways suggestive of alternative ways of coming into being with the making itself. In the generating of artworlds, we commit to considering: the fallacies of crown land and the illusioned provincial borders; compulsory participation in capitalist structures and state-sanctioned productivity; the erroneous delineation of reserves that make up an insulting percentage of so-called KKKanada where few have access to clean drinking water among other basic necessities; gendered violence and laws that uphold it; the infectious binary thinking that targets our most sacred teachings carried by 2Spirit, Queer and Trans knowledge keepers; the overrepresentation of our BIPOC kin who also are subjected to police brutality, forcibly taken into foster care and disproportionately and unjustly incarcerated; the criminalization of Land and Water protection in support of the ongoingness for generations to come; the derailment of media coverage when apocalyptic viruses become centered over Indigenous Land; Sovereignty movements, only further targeting our street-involved community members or those living on reserve with limited health care; the genocidal crisis of our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Trans and Two-Spirit relatives; and the violent dissection of our territories and our bodies into reserve/city and rural/urban dichotomies. The state’s abuse of power comes as no surprise — continuously understating the genocidal + ecocidal crisis as an explicit ploy for erasure, assimilation and eradication of our relatives. At the onset of a virus, the government bodies were able to implement immediate closure of daycares, schools and cultural institutions across this nation state, but after the release of an inquiry considering a century-old genocide of our women, girls and two-spirit relatives, the man camps remain, still.

Present-day Indigenous lived experiences are saturated with these realities. Far from a disorder, trauma is but a reaction to a world in which our people are routinely threatened, injured and murdered at the hands of colonial violences: current, ancestral, historical, individual, collective. When the emotional envelope which accompanies and sustains our mind–body–spirits while in constant duress and attack under settler colonial surveillance and control, in order to survive—we make worlds with kin. Through world-making and future-imagining, we have developed a reciprocal lexicon, one that allows us to (re)envision our realities, our relationships, our ways of seeing and being seen.

Just as alliance is braided inter-nationally and we have come to understand ourselves through being unified as “Indigenous” peoples, our digital kin have established new takes on centuries-old misnomers and hashtag culture-proliferated “NDN.” This shorthand is now widely used across screen-based Indian Country to self-refer. NDN is not, not an acronym for Not Dead Natives and through this naming, we are reminded that those of us that are still here, exist together. Together, across Lands and Waters, we are dismantling the colonial borders and restraints that keep us apart, to create sovereign and dynamic spaces to witness, to care, to hold, to love.

In this time, our time, we have witnessed great mobilization—growth, from seed, that has taken place in cyberspace. Woven together by hashtags, finding budding kinships over image-based stories that disappear post-tap: we acknowledge that a physical coming together, despite the threat of cross-contamination, is grounds for true resurgent practices rooted in radical care. We have witnessed, this past spring, the effects that containers of isolation have in exacerbating our levels of loneliness and withdrawal. Loving in NDN time has never been about pacing nor containing. Elixir of excuses and toxin of a measurement, NDN time does not take for granted the ongoingness of the other. Our resilience and continued existence under the pressure of genocide, ecocide and suicidal ideation, leaves a feeling of speed at the heart of loving. As if we need to love hard + fast before one of us disappears. Risking a compression into something (too) solid, whereas our beings, infinite as they are, stretch far beyond our skinned mass. This rabbit speed at which we are made to love each other is not akin with privilege; there is a desire to deserve the endless time that we crave to love each other over. 2S42S love, particularly, has carved out space for us to weave these threads, the ties that lift, to love wholly and fully—a love with honour at its core, a love that encourages a return to relational multiplicity, a love that co-constitutes our existence, a love enacted across constellations, a love in action through currents—love as Ceremony. When we world into our realities islands of decolonial love, we not only survive, we transcend in so to transmute. NDN love works at light speed, crossing generations, lifting epigenetic coding and reigniting the fire from the coals our Ancestors protected.

To consider kinship, in regards to curatorial practice, is to consider a deep sense of care and accountability. We must engage these responsibilities to assert mechanisms of support, of truths, of transformability—with and for those whom we hold most dear, those who have come before and those who are yet to come. We could not center kinship as a thematic without the work of so many: the artists and the writers, the theorists and practitioners, the aunties and the uncles, the Elders and the young ones . We are able to center kinship in our work on grounds of resilience of the Medicines of our 2S Indigiqueer warrior kin existing in the margins and carrying the teachings outside the logic of containment. As we move through the lineage(s) of kinships, we recover a basketry that is rooted in love. Love as a permutable force that guides us into our pasts, presents, and futures. Love is, at once, ancient and blossoming in which our kin, known and unknown, are shaping into endless, life-giving, affirming knowledges that preserve us. We braid work, in so, to continue to believe there is life after NDN love.

The sinewed nature of this work collapses notions of the proprietary. We fold individual success into collective abundance. We hold in high regard these opportunities entrusted to us by Elders and Kin—in form and function, this work is for Us. Us, a togetherness larger than nationhood and community ties, a togetherness through root systems and networks of Love. As Indigenous peoples participating here as members of larger diasporas and existing at various intersections, we are not making claims to be in positions of knowing, rather, hoping to extend both proverbial and physical hands in trust. Our relations and our Ancestors have led us to this place through a multitude of paths and while we are here, we hope to see and be seen, to carry one another in accountability, to equitably honour loss and gain, and to find comfort in knowing that it is unimaginable to shoulder this work and this world alone.

1. This work could not be imagined or activated without the precedence and guidance of our kin, in thought, theory and Spirit: Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Kim Tallbear, Lindsay Nixon, Billy-Ray Belcourt, Joshua Whitehead, Marie-Andrée Gill, Smokii Sumac, Tommy Pico, Qwo-Li Driskill, Lee Maracle, Gwen Benaway, Arielle Twist, Ma-Nee Chacaby, Cher, Okay Kaya, Joce Two Crows, Jeremy Dutcher, Jenny Holzer, Renee Linklater, Jolene Rickard.

The James Bay Project: Rainer Wittenborn’s and Claus Biegert’s collaboration with the Cree

Arnd Schneider

“We knew: only with the Cree would we be able to create an exhibit about the conflict at James Bay. Very early during our research we came to the conclusion that the Cree have to be first in reviewing our work before we would present it to the public in Canada (starting at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Montreal), the US, Brazil, Europe and Thailand, eleven venues in total.” (1)

In 1979/80, two Germans, the visual artist Rainer Wittenborn, and Claus Biegert, a long-time member of Survival International, broadcaster and writer on North American Indigenous affairs, visited the Cree First Nation of the James Bay Area / Euyou Istchee in Northern Québec, whose area was threatened by huge hydroelectric plants, and whose traditional hunting grounds would eventually be destroyed by flooding. The five-month project included a detailed survey of the area, many interviews with Elders and knowledge keepers in different Cree villages (for example, in Eastmain, Chisasibi, Wemindji and Mistissini), and also politically embarrassing questioning of the managers of the James Bay Energy Corporation in Montréal. Wittenborn and Biegert had presented their project to the Cree Grand Council in Val d’Or and obtained their active co-operation. Wittenborn and Biegert, both with track records of working on ecological topics and threats to indigenous peoples, had read about the situation in the James Bay Area and wanted this to make the focus of a new work.

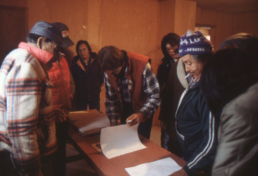

The artists promised the chiefs of the Grand Council that in two years, once their research and art works were completed, they would return and show their work in the new school at Chisasibi, where the Fort George community had been relocated. It was in Chisasibi that the Canadian tour of the exhibition opened. This was a deliberate attempt to expose the often self-serving politics of artists, anthropologists, photographers, and journalists, which a Cree woman, Susan Pshagumskum in Wemindji, had spelled out in very frank terms: ‘They come up here and milk us dry .., and then they never show up again’ (2). The work of the Europeans was accepted and appreciated, not only by the students but also by Elders, whose weekly council meetings Chief Samuel Tapiatic moved to the school building in Chisasibi in order facilitate the widest possible access to the exhibition.

The exhibition had three themes: The Nature, The People, and The Complex. The Nature focused on the environment and basis of Cree livelihoods, now threatened by the hydro-electric plants. The People put emphasis primarily on the daily lives and hunting culture in the different villages Wittenborn and Biegert visited. It also featured those who had come North to change everything, i.e. the contract building workers (figures 1 -9: JBN 8, JBN 13, JBN14, JBN16,JBN18, JBN28, JBN29, JBN30, ‘James Bay Worker and Kenny Blacksmith’) . Finally, The Complex (figure 10 JBN19) documented the huge construction works for the hydro-electric plants, dams, workers’ villages and already flooded areas. Since the 1960s the government of Quebec had been making plans for the exploitation for energy use of the vast water resources of Northern Quebec. The James Bay Hydroelectric Project for large hydro-electric plants was implemented from 1971 onward by the James Bay Development Cooperation. However, the government did not consult with the First Nation Cree and Inuit peoples of the area, and only after legal opposition by the First Nations and various court rulings, in 1975 signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, which paid compensation, and legally enshrined fishing and hunting rights, but also implied the loss of certain lands for the First Nations. Their territories had changed beyond recognition, and eventually an area the size of Belgium had been flooded.

The James Bay Notebook was a principal part of the exhibition, and consists of 60 pages (110cm x 75cm) available in a box and arranged as fold outs, of which we show a selection here from photographic scans. On these pages, broadly chronological and in diary form, large-format collages of text, images, and hand-written annotations bear witness of the journey the artist and the writer took through Cree lands. The exhibition, and especially The James Bay Notebook, incorporated plants collected, traps and other items donated by the Cree, as well as wild fowl (such as Canada Goose and Black Duck), which were put in transparent plastic bags fastened to the pages; here figures 11 & 12: JBN23, JBN25). The James Bay Notebook is crafted in the signature style developed by Wittenborn, already in his series of drawings “Amazon Basin” (1975/1976) where he combined ‘scientific’ information (such as satellite maps) with intricate pencil drawings of the environment and livelihoods of Amerindian peoples threatened by the destruction of the Amazon rainforest. (3)

In the James Bay Notebook, the meticulously executed drawings of environment, animals, hunting equipment, and people, show not only the skills of the highly accomplished draughtsman, but a craft which, beyond virtuosity, gains in expression and sincerity from the time spent in dialogue and learning with the Cree.

A central part of the work is the herbarium, with classifications according to both Western and Cree terminology. On 17th October 1979, Wittenborn showed the plants he had collected so far to Cree Elders in Wemindji, among them the very knowledgeable ElderGeordie Georgekish (figures 13 – 16: ‘Plant inspection with Cree Trappers of Wemindji’, ‘R Wittenborn with plant collection’, ‘Wemindji 1979 Geordie Georgekish (r)’, ‘Wemindji -Wittenborn with Cree trappers’). As suggested by one of the young Cree helper who had provided the contact with the elders, tobacco was later distributed among them as a recognition of their classification work.

Wittenborn writes in the travel diary:

“I am laying out the folded pages (with the plants) on the table. We ask for the names and the usage of the plants. With the help of the translator, Claus Biegert notes down for each specimen, its usage as material, food, and medicine. Below the Latin names, the teacher for the Cree language writes down the Indian names with the syllabic characters in Cree. Rarely, there is disagreement, then the plants go through the hands of all. (…) Geordie Georgekish, maybe already over seventy, seems quieter than the others, has the most comprehensive knowledge, decides as the last, and seems to be the unchallenged authority here. Plants here are something else than just material of study. Already the nomenclature is different, knows no genera, orders, families, sub-families etc. as in our system. The plant stays in direct connection to people and animals, is part of daily life, of daily experience in the bush. There are no problems with the lichen which are difficult to classify. The species Cladonia, for example, Geordie identifies as ‘Wapiscamik – what the caribou eat’. ‘Waekunk’, the black-dotted stone lichen, which we couldn’t identify in Lac Hélène, is known as ‘bread-lichen’; it is ground as flour in hard times and then baked as flatbread.” (4) (figure 17 ‘James Bay Plant collection’)

Both anthropology and the arts practiced by Westerners have a long history of appropriating from Others who had previously been colonized. However, in terms of artistic excursions into ethnographic terrain, and what later became a growing field of collaboration between contemporary artists and anthropologists (‘the ethnographic turn”), the James Bay Project was far ahead of its time.(5) In fact, Wittenborn and Biegert’s artistic research project with First Nation communities provided a substantial challenge to the academic discipline of anthropology, which for too long, and marred by its colonial entanglements, had taken a prerogative on the representation of Others, and only in the mid-1980s began to seriously question its own practices. This was somewhat preceded by the strong political stand of the small radical brand of action anthropology, where anthropologists supported First Nations in legal fights for land and other rights, and which also inspired Wittenborn’s and Biegert’s James Bay Project.

The particular value of The James Bay Bay Project for present and future artistic engagements with First Nation communities lies in its strong political advocacy, and committed ethical stance – present in every aspect of the project, from planning, gaining permission and mutual interest, respectful dealings during the research, and return of results through exhibition and catalogue to the Cree (including, upon the Cree’s invitation a return visit and new exhibition Amazon of the North in 1995) (6). It speaks to the uncondescending, ethically highly conscious attitude of Rainer Wittenborn in this respectful collaboration with the Cree, that when asked in Mistissini by Louise and Kenny Blacksmith if he – an accomplished draughtsman – could also draw plants and animals, he encourages them to make their own drawings and herbarium, rather than providing the couple with his version (‘which could be a very beautiful piece of work, but it would be more my own and not any longer theirs’, as he records in the published travel diary of the project) (7). It is along such lines of respect and ethics of collaboration, where joint artistic research with outsiders can be advanced on First Nations’ terms and own interests.

Acknowledgements

I thank David Garneau for the invitation to write this essay, and Rainer Wittenborn and Claus Biegert for their generous time and help in locating artistic works and materials. All translations from the German are mine. Dedicated to Cree First Nation of the James Bay

Area / Euyou Istchee.

Notes

(1) Wittenborn, Rainer and Biegert, Claus, “Answers to questions by Arnd Schneider and Christopher Wright” (Dialogues), in: Contemporary Art and Anthropology, eds. Arnd Schneider and Christopher Wright, Oxford / New York: Berg, 2006, p.144.

(2) Wittenborn, Rainer and Biegert, Claus. James Bay Project: A River Drowned by Water. Montréal: Museum of Fine Arts, 1981. p. 268

(3) Wittenborn, Rainer. “The Amazon Basin”, Rainer Wittenborn Landscape Management / Transmitted Pictures, Münster: Westfälischer Kunstverein /Ludwigshafen: Kunstverein, 1977/1978.

(4) Biegert, Claus and Wittenborn, Rainer. Der groe Flu ertrinkt im Wasser: James Bay: Reise in einen sterbenden Teil der Erde The great river drowns in water: James Bay: travel to a dying part of the earth. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1983. p. 67

(5) Schneider, Arnd, “The Art Diviners”, Anthropology Today, 9 (1993), 2, pp. 3-9, and “Uneasy Relationships: Contemporary Artists and Anthropology”, Journal of Material Culture, (2), 1996, pp. 183-210. Also, Foster, Hal. “The Artist as Ethnographer”, The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Culture. Eds. George Marcus and Fred Myers, Berkeley: University of California Presss, 1995.

(6) Wittenborn, Rainer (in collaboration with Claus Biegert). Amazon of the North. Middletown, Connecticut: Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery Center for the Arts Wesleyan University, 1995.

(7) Biegert, Claus and Wittenborn, Rainer. Der groe Flu ertrinkt im Wasser …, p. 140.