May 3 – June 22, 2014

Opening reception: Sunday, May 4th from 2-5pm

Jaime Black (Winnipeg, MB), Julie Buffalohead (Saint-Paul, MN), Hannah Claus (Montréal, QC), Keesic Douglas (Toronto, ON), Merritt Johnson (New York, NY), Nadia Myre (Montréal, QC), Mike Patten (Montréal, QC), Tanis Maria S’eiltin (Bellingham, WA), Michael Anthony Simon (Seoul, Korea), Adrian Stimson (Saskatoon, SK), Anna Tsouhlarakis (Washington, DC).

Stewart Hall Art Gallery

176 Du Bord-du-Lac – Lakeshore Road

Pointe-Claire (QC)

Humans are storytelling animals. Story is a primary structure through which humans think, relate, and communicate. We make stories, tell stories and live stories because it is such an integral part of being human. The myths we live by actively shape and integrate our life experience. They inform us, as well as form us, through our interaction with their symbols and images.1

In the nearly five-century long history of colonization, de-colonization and post-colonization, it is rather surprising that there is no recognized aboriginal system of education in Canada.2 While the historical reason might have been to serve the colonizing strategy of cultural assimilation, notably with the founding of residential schools a few decades ago, the reason for this astonishing actuality today is the sign that their pedagogical system is still underestimated by many. The Canadian scholar Judy Iseke remarks that the central focus of Indigenous epistemologies, pedagogies and research approach is very different from that of the European tradition of magistrate teaching that prevails in our society.3 In fact, one common trait to most native cultures is the communication of knowledge through stories.

While storytelling as a system of communication may be ancestral— in fact myths and legends have been the keystone of teaching in most cultures – it remains an incredibly effective tool for teaching even today. Annie Murphy Paul reports in an article in the New York Times that neuroscience research has determined that parts of the human brain are only activated by narrative-based knowledge.4 Information is often remembered more sharply and for a longer continued period of time when it is associated to a narrative, as opposed to when it is delivered in a dry bullet-point form. Nevertheless, storytelling is still generally neglected by conventional pedagogy. As pointed out by Sandra E. Sherwin-Shields, we live in a world dominated by the perspective that knowledge is rational, irrefutable, and objective.5 Storytelling opens the door to a different kind of knowledge, one used to organize and interpret collective and individual phenomena as to make sense of personal and shared experiences, one that connects us to our environment and to others, one that takes into consideration our subjectivities.

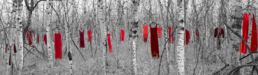

For the second edition of the Contemporary Native Art Biennial, I chose to invite contemporary native artists – many whom are also teachers in the post-secondary Canadian system- to share stories that are brutally contemporary and incredibly relevant to current times. Some of the stories are very personal, while many tell more prevalent stories, principally those of the ecological decline. Many of the most renowned intellectuals agree that Indigenous nations are leading the way in ecological awareness. Social movements such as Idle No More are inextricably linked to the environmental cause. Noam Chomsky, perhaps one of the most important minds of our era, is famous for underlining the importance of First Nations’ activism in terms of ecological policies. The artists included in this important exhibition do not merely ring the emergency bell for ecology, but through storytelling, they aim to teach us to respect and celebrate nature in its complexity and for its fascinating design.

It is notably the case of Michael Anthony Simon’s Loud Whispers for which he lets spiders form their webs in his studio before releasing them back into nature. He then paints the spider webs in a transformational manner that evokes dream catchers. By subverting the ordinary, the banal he upends perception and shifts the focus to the quiet and often unnoticed. He also forces viewers to reconsider something seen as unimportant as a spider web and thus achieves to change their relationship to it. It is as if the work teaches us that caring for the environment and paying attention to nature will act as a dream catcher that has the power to prevent the ecological nightmare that currently constitutes a menace to our planet.

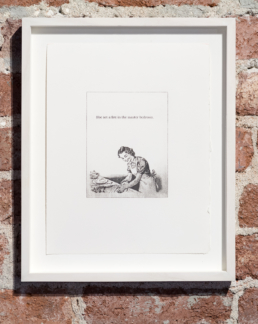

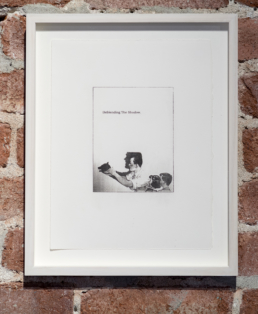

Da-ka-xeen Mehner found in photographic archives images of a curious character that strangely enough carried a phonetic variation of his name. Through these old photographs, he investigates how the story of the Tlingit people was told in visual history. He reinterprets it, creating a link between the past, of how the story of his people was told and the present and of how he chooses to recount it today. His images reveal ideas of truth and of fiction as existing side-by-side. Like Scott Benesiinaabandan, his work addresses the need of the human brain to construct a narrative to make sense of the world we live in. In his series Psychometry, Benesiinaabandan refers to a psychic technique traditionally used by many indigenous people by which one can “read” history via the energy locked into physical objects and spaces. It is a practice of indigenous storytelling that empowers individuals to be sensitive to their environment.

Keesic Douglas’s photographs offer another perspective on urbanism and its effect on nature. He took photographs of truncated tree trunks. These dismembered trees are visually reminiscent of totems, but appear disregarded, abandoned, forgotten and even harmed. Upon examination of these fascinating photographs, the timber remains recall, in an interchangeable manner, the dire fate of both nature and of native cultures. Studies report that there are more natives nowadays than ever before, with more than half of the indigenous population living in urban centers. As a matter of fact, natives are measured to be the fastest growing population in Canada, while unjustly aboriginal languages are in decline, in many cases they are near complete extinction.

The importance of the passing of knowledge in the context of the current cultural crisis that many native cultures face is eloquently addressed in Adrian Stimson striking Beyond Redemption. A bison seem to be leading an assembly like a teacher amongst his pupils. However, his ‘apprentices’ are just husks on crosses, the products of years of cultural discrimination. They appear undisposed to ingesting knowledge, unreceptive to the words of their master, insular to their own culture. This large installation gives a grim picture of the education crisis in native communities nowadays.

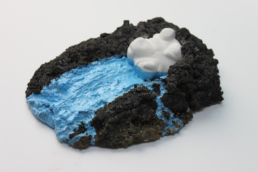

Both Hannah Claus and Amelia Winger-Bearskin address the Iroquois myth of Haudenosaunee. It tells the story of Sky Woman’s fall from Sky World through the hole left by an uprooted tree. As she is falling, waterfowl come together to catch her, placing her on the back of a great turtle who accepts to receive her. In this teaching clouds represent creation, creativity and community. Like clouds, communities are composed of an infinite number of shifting and active individual particles that come together to create a common whole.

Storytelling unlike European pedagogy leaves knowledge undefined, subject to interpretation, and thus, fosters an ideal context for change. To tell a story in pedagogical terms is to perform a meaningful individual and social act. This is precisely what the artists included in the exhibition request: that we engage with the stories told to us and that in return we become more aware of our environment, of our experiences, of others with whom we are sharing our lives. The compelling works included in Storytelling are informed by the past, but they are desperately addressing the present. They make us more aware of the potential political, cultural and ecological dangers of an overall careless society by positioning our stories and our experiences at the center of a powerful movement for change.

1. Gregory Cajete, Look at the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Learning, 1994: 116

2. Rosalind Hampton “Indigenous control of Indigenous education” in The McGill Daily [web]: http://www.mcgilldaily.com/2014/03/indigenous-control-of-indigenous-education/

3. Judy Iseke « Storytelling as Research » in International Review of Qualitative Research vol. 6, no. 4 (Winter 2013) : 559.

4. Annie Murphy Paul “Your Brain on Fiction” in New York Times [web]: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/18/opinion/sunday/the-neuroscience-of-your-brain-on-fiction.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

5. Sandra E. Sherwin-Shields, Touching Spirits: Story and Relationship in an Aboriginal Teacher Education Program, University of Saskatchewan (1998): viii.